Historical Article : Me 264 : the Luftwaffe's First 'America Bomber'

Raul Colon looks at the Luftwaffe's efforts to develop its first strategic bomber. The result was the Messerschmitt 264, capable of bombing US cities and protecting the U-boat fleet in the Atlantic. However the project ended with only one Me 264 completed.

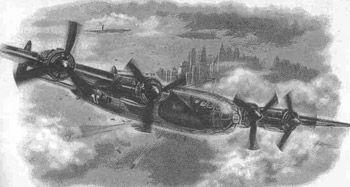

Me-264 Artist Impression

The term America Bomber evokes echoes from a distance past. A time when Adolf Hitler’s Thousand Years Reich was fighting for its existence barely ten years after it was conceived. A time when Germany, haplessly engaged in a two front war, cried out for a wonder weapon that can strike back at her adversaries. A time that came and passed without anything built that closely resembling what that term described. The concept of the “America Bomber” did not had its origins in the early 1940s as sometimes is described in history books. In fact, the idea of a long distance bomber that can deliver a massive payload to an enemy far away was the brainchild idea of an obscure Luftwaffe General, Lt. General Walther Wever. Wever, born on the German eastern province of Posen, was an early advocate of strategic bombing. He saw action during the Great War and rose steadily through the ranks in the inter-war years. In 1932, Wever was appointed Chief of the Air Command Officer, a cover post designed to fool the allies. In reality, Wever was the Chief of the Air General Staff, one of the most important policy making post in the German armed forces.

As the clouds of war began to appear over Europe, Wever, ever the visionary, anticipated Germany’s need for a long range heavy bomber force. Wever was committed to the concept of strategic bombing ever since reading about Sir Frederick Sykes work on the future of the aircraft in a total war, published in December 1918. In accordance to his vision Wever requested in the spring of 1934 that Germany’s major aviation companies submit blue prints for the design of a platform capable of achieving his vision. Wever requested that the new bomber be a four engine plane with a minimum bomb load of 3,300 pounds and an operational range of at least 1,250 miles. At first, the new concept was to be known as the Ural Bomber because of Wever’s projected enemy, the vast Soviet Union, had its aircraft industry center deep inside the Ural Mountains, and there was where he wanted the Luftwaffe to concentrate its bombing campaign. Because of his visionary ideas and the passion from which he pursue them, Wever was outcaste by many of his peers and mostly ignored by his superiors. Nevertheless, Wever pressed on, and in May 1936 he published the first Luftwaffe training book in which he declared that the main mission of air power is to carry the war to the enemy’s power structure centers and destroying the people’s will to resist.

Meanwhile, the Dornier Company was hard at work on the development of Wever’s vision. On the morning of October 28th, 1936 that vision became one step closer to being realized when Donier’s Do-19 made its maiden flight. Two months later, Junker’s entered the fray with its Ju-89. Each plane would go on to underachieve in its primary mission profile. At the same time, and while Dornier and Junkers fought over which will be the first to produce the Ural Bomber, a new player entered the field.

Model of the Messerschmitt Me-264

The famous German aviation pioneer Willy Messerschmitt began working on the concept in the summer of 1937. Designated project 1061, its goal was to produce a serviceable four engine bomber with an astonish 12,428 miles of operational range and an 11,000 payload capacity by the early 1940s. Paul Konrad, Waldemar Voigt and Wolfgang Degel; the aircraft’s three main designers, began at earnest putting up a blue print for the new bomber. The plane’s mockup was completed in May 1940 and Messerschmitt himself presented it to Adolf Hitler a month later. Hitler was so impress with the new design, that he ordered the plane to be place on production status. Soon thereafter, project 1061 would change call signs, now the program would be named the Me-264. The original Luftwaffe order called for four units, with an additional batch of 24 to follow soon after. At the same time, engineers at Messerschmitt were working on a six engine, modified version of 264 that would be able to extend the aircraft’s range and bomb load capacity.

Meanwhile, the German Navy, in conjunction with the Luftwaffe, began exploring the possibility of fielding a complementary long range air arm to augment their U-boat campaign in the Atlantic. Four planes were reviewed for this task in January 1941. The Me-264, Focke-Wulf’s FW-200, the He-177 and the Bv-222 float plane. The 264 was the clear winner. But before the aircraft could be made operational, the Luftwaffe’s famous Technical Department began to twinkle with the original design in an effort to extend the plane’s range and payload. Plans were drawn for the 264 to become the world’s first operational aircraft to be refueled at mid air. In the spring of 1942, there were a successful German mid air refueling operation between a Ju-90 and Fw-58. Beside mid air refueling, designers also toyed with the idea of adding two additional engines to the fuselage in an attempt to stretch the bomber’s range. As the 264 program continued to evolve, questions began to rise about the aircraft’s real operational range and therefore, its mission profile. In the month of April 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Peterson headed a fact finding commission into the main Messerschmitt 264 facility at Augsburg with the purpose on reviewing all existing data regarding the aircraft program and its possible applications. He came away from the inspection impressed with Messerschmitt progress on the project and related the company’s intention of having a full operational squadron by the fall of 1943. In the meantime, frequent part delivery delays were beginning to plague the project. By the summer of 1942, many inside the Luftwaffe’s higher brass began to question Messerschmitt’s original statement that the plane will be operational by late 1943. In fact, there were some rumble lings inside Herman Goering’s inner circle about the feasibility of canceling the entire program. Fortunately for the 264, the influential General Freiherr von Gablenz, after conducting his own inquire about the state of the program; recommended that because of the leap in technology that the 264 represented, the project would probably require more time. This “leap in technology” sentiment appealed to the Luftwaffe’s top brass sentiment of superiority. From that moment on, they were on board with the program, although not for long.

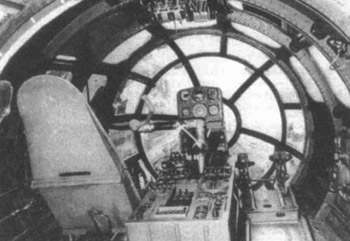

Me-264 Cockpit

December 23rd, 1943, a lone Me-264, designated V1; took to the air for the first time. It was an awesome sight. The aircraft had a wing span of just over 141 feet, roughly the same as an American B-29 heavy bomber. Its airframe length was 66 feet, exactly the same as a modified B-24. On that day the aircraft flew flawlessly. Luftwaffe officials on the ground were more than impressed, they were at awe. With this maiden flight, the America Bomber concept, the project Wever so passionatly advocated for in the mid 1930s, was fast becoming a reality. As the aircraft’s testing phase commenced, new difficulties threatened to slowdown the program. Chief among them was the availability of engine parts and aircraft systems. At this time of the war, all of Germany’s aviation-related industries were operating above capacity. Another player entered the court. The German Navy, since early on, had press Germany’s aviation companies to produce a long range maritime prowler to assist their beleaguer U-boat fleet in the vast Atlantic. They lobbied hard, with the newly appointed Commander in Chief of the German Navy, Admiral Karl Donitz, taking the lead; for the shifting of the 264 mission profile. His pressure paid off when in July 1943, Hitler decided that the America Bomber would now be assigned to the Navy’s submarine force. He told Luftwaffe commanders and Messerschmitt officials that the lack of sufficient numbers of planes would make bombing American cities seen as an act of desperation in the part of a dying armed force. This decision did not mean that work of the program ceased. In fact, modifications to the engines house structure as well as its fuselage began in late November 1943. At the same time, work began on the second and third planes of the first batch, properly designated V2 and V3. But by this time, the fortunes of war had turned on Germany. Assaulted from all sides and in desperate need of fending off a massive Soviet land army, Hitler gave the order to terminate the 264 program in September. On the 18th of October 1944, the Reich marshal Technical Order Number 2 officially cancelled the project. And so, Wever’s dream of a strategic Luftwaffe force died with that order.

-

Sources:

- Aders, Gebhard. History of the German Night Fighter Force 1917-1945, Jane's Publishing Company, London, UK, 1978.

- Bekker, Cajus. The Luftwaffe War Diaries, John Macdonald & Co., London, UK, 1966.

- Young, Richard A. The Flying Bomb, Ian Allan Ltd., Shepperton, UK, 1978.

- Irving, David. The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe; the life of Field Marshal Erhard Milch, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, UK, 1973.

Article copyright © 2008 Raul Colon, rcolonfrias@yahoo.com

Last Modified: 24 February 2013

Update log:

02/24/13 Upgraded layout

Back to Index

Back to Index